-

Fly Fishing For Salmon on Great Lakes Rivers

One of my clients holding a large Great Lakes Salmon he caught on his fly rod. We hooked over 20, and saw about 300 swim past us. I’m going to share the exact strategies, secret knowledge, and the same setups I’ve been using to guide Great Lakes salmon for the last 25 years.

If you’ve ever wanted to know what a top fly fishing guide’s methods and setups are to catch salmon in the rivers, this is your chance.

Yes, I’ve been guiding the rivers of Ontario for salmon for 25 years using multiple methods of fly fishing, such as Euro Nymphing, Indicator nymphing, Streamer fishing, and Spey fishing.

Using multiple methods has enabled me to be a better fly angler.

I’ve also fished the rivers of New York, Michigan, Illinois, and Wisconsin for salmon and steelhead for the last 36 years.

I can assure you that the same methods I use and have perfected to ensure my clients catch the most salmon possible, in all types of rivers, and in all conditions, work everywhere around the Great Lakes.

In fact, I have observed that the top river salmon guides all over the Great Lakes are using the same methods and setups.

To catch Ontario salmon, or any Great Lakes salmon, once they enter the river, you need a few things.

- A perfect presentation – EVERY TIME

- A suitable fly, or multiple flies, based on the river and the conditions.

- Where the salmon hold, feed, and travel routes.

- A knowledge of the salmon runs, run timing, and which rivers are best.

- The right setup for the method you want to use

- The right gear

I’m going to discuss all of these in this article.

A Great Lakes Coho salmon held by author and guide Graham. This was one of many caught on the fly rod. For general information on fishing for salmon around the Great Lakes, go to our Fishing For Salmon page.

What Fly Fishing Method is Best For Great Lakes Salmon

One of my clients fighting a large Great Lakes salmon with a fly rod Fly fishing for Salmon can be done in a few ways or with a few different methods.

Here’s the thing: the guy who is adaptable catches the most fish. I’ll discuss that a little more below.

- Nymphing with Indicators

- Euro Nymphing, also known as tight line nymphing

- Streamer fishing

- Spey fishing

- Dry Fly fishing

In smaller and shallow rivers, fly fishing using indicators or Euro Nymphing can be very effective at landing salmon. I use both and will change based on the type of water and where the salmon are holding.

Large and small streamers can be deadly for salmon. rotate between dark and bright colors to determine what they want. In deeper or slower rivers, it’s hard to beat indicator fishing or streamer fishing.

Swinging flies or stripping streamers can also produce in both deep and shallow waters, and at times, you will catch some very big aggressive salmon.

Fly Fishing For Salmon With Indicators

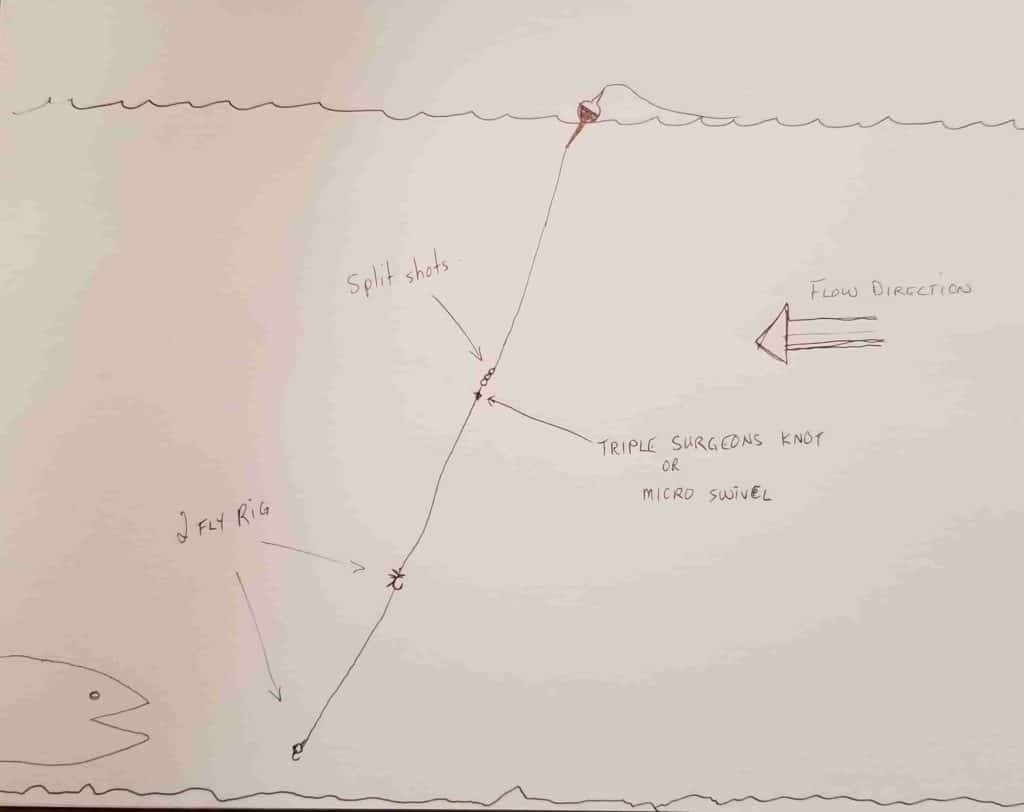

Fly Fishing For Salmon with indicators requires a large indicator, some split shots, and 1 or 2 flies, along with the right size leader and tippet.

Why Use Indicators When Fly Fishing For Salmon

Indicator fishing is often the most productive way to fly fish for salmon in many situations along the river.

When the salmon first enter the river, they move fast, and they don’t slow down much because they are in an unusual and less safe environment, and they want to cover as much water and get as far up the river as possible.

Eventually, they will get tired and start to rest or hold for short periods of time at the base of the next rapid or in deeper, slower pools. If the water gets too low, especially during high light periods of mid-day, they can often hold in these bigger deeper spots all day or until it becomes dark enough that they feel comfortable moving in the shallower water again.

Once the salmon are in these pools and are resting, they are most likely to grab a fly, and the most productive method in these slower and deeper water spots is with an indicator.

A well-presented and slower-moving presentation under an indicator is most likely to get the aggressive and even the less aggressive fish to bite.

The Best Indicators For Salmon Fishing

I cover the water systematically and make sure I don’t miss any spots. The key is covering the water from one side to the other, but also covering multiple depths, meaning, ensure you are at least a foot from the bottom, as well as cover the areas 4 feet off the bottom for suspended fish. Some indicators do not float well or may even break your line, and many do not allow the angler to get better angles for a better presentation, so using the right indicator is important.

Depending on conditions, which include the depth and speed of the spot I want to fish, I use two types of indicators when guiding and fly fishing for salmon.

For deeper, slower water, I choose to go with a taller, thin float-style indicator similar to what the float fishing and centerpin guys use. Using this type of indicator can greatly increase the amount of salmon you will catch in this slower, deeper water.

One of my clients fighting a large salmon. During the fall you could catch salmon, steelhead, and even large brown trout all in the same spot. This is not the traditional type of indicator you would expect, but it works, and it works well, in fact, for many reasons that are hard to explain it almost always works better than a traditional indicator if you use it correctly.

The Raven FS 3.8g float allows the angler to present the flies at a better angle for fish that are in slower, deeper pools, but it can also work the faster water too.

Salmon in these deeper pools can be suspended at different depths, and this float is easily adjustable, and it still casts OK. Make sure you go with the bigger 3.8-gram float for salmon, especially if you are using more than 3 split shots.

Salmon Leader Set-Up and Proper Angles

The Raven FS 3.8g float also allows the angler to suspend the flies at multiple levels without dragging the flies across the bottom.

You could even add a third fly where the split shots are in this diagram, in case any salmon are suspended high in the water column. You can also add a weight between each fly instead of above the flies.

Even if one fly is dragging across the bottom where most fish do not usually see it, the top fly is usually in the strike zone.

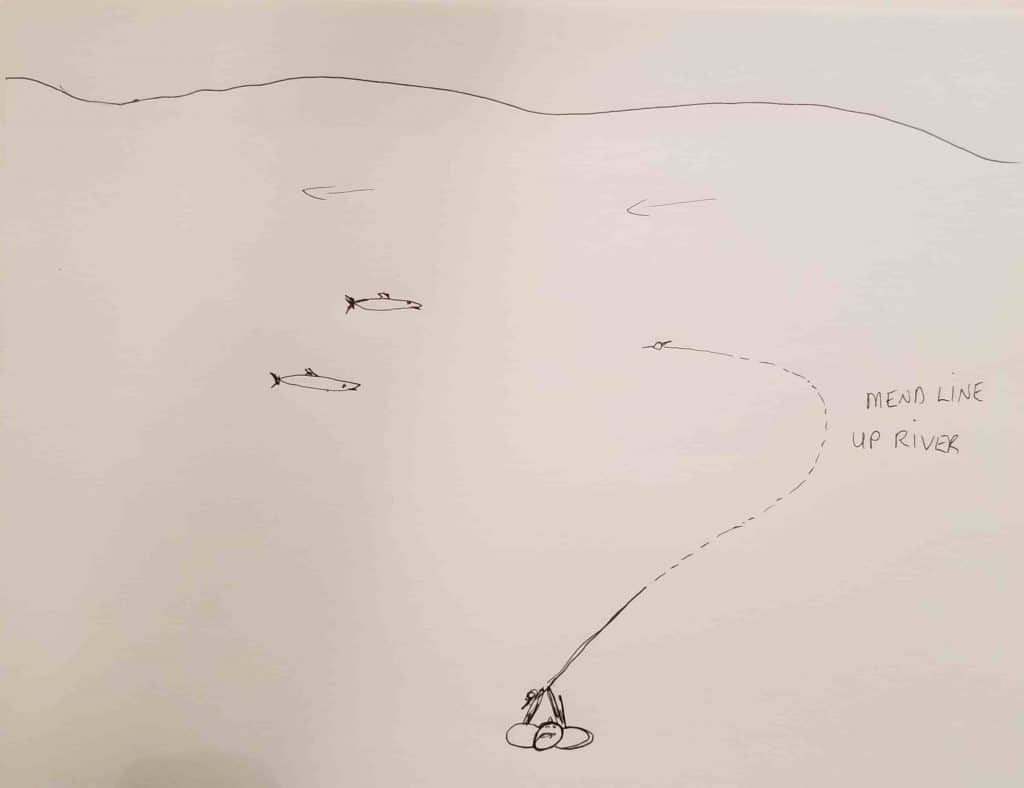

You also want to maintain this angle by mending the fly line as far upriver and out towards the indicator as possible. See the Diagram below.

Doing so will create micro drag, which will hold back your indicator slightly so you get the angle you see in the picture. You want a straight up-and-down angle with your fly just slightly in front of your float. If your fly is trailing behind your float, you will be dragging your fly, and you WILL catch fewer salmon. Sometimes 80% less…

If you can perfect this angle with proper mending, you will greatly increase the number of salmon you will hook.

Using this suspension style of nymphing instead of the traditional style of dragging your weights and flies across the bottom will always work better and is what I use when fishing myself and with my clients.

The old traditional leader setup that you may still read or hear about of having the length of leader between the float and the bottom fly being 1 1/2 to 2 times the depth of the water is old school and not as effective as suspending the flies and keeping them off the bottom.

Egg Sucking Leeches are great for salmon Just watch the underwater video of trout, salmon, and steelhead feeding below the surface, and you can clearly see that they feed sideways in a side-to-side manner,r and they also feed upward.

Rarely will you ever see them feed down into the rocks to pick up a bait, so it only makes sense to keep your flies off the bottom, and based on my years of experience, it’s always more productive to suspend your flies off the bottom.

How To Indicator Nymph For Salmon Better

This picture demonstrates an angler who has mended his fly line upriver to achieve the best angle for the leader and a much better presentation overall.

For the more traditional indicator that anglers use, I like the 1 1/2-inch Thill indicators seen here the best.

I prefer a two-tone indicator for teaching and for fishing because it helps the angler determine the angle of their flies. If the angler is wrong, you will catch fewer fish.

I use it in a similar fashion as the other indicator and with the flies suspended and the line mended upriver.

How To Nymph For Great Lakes Salmon

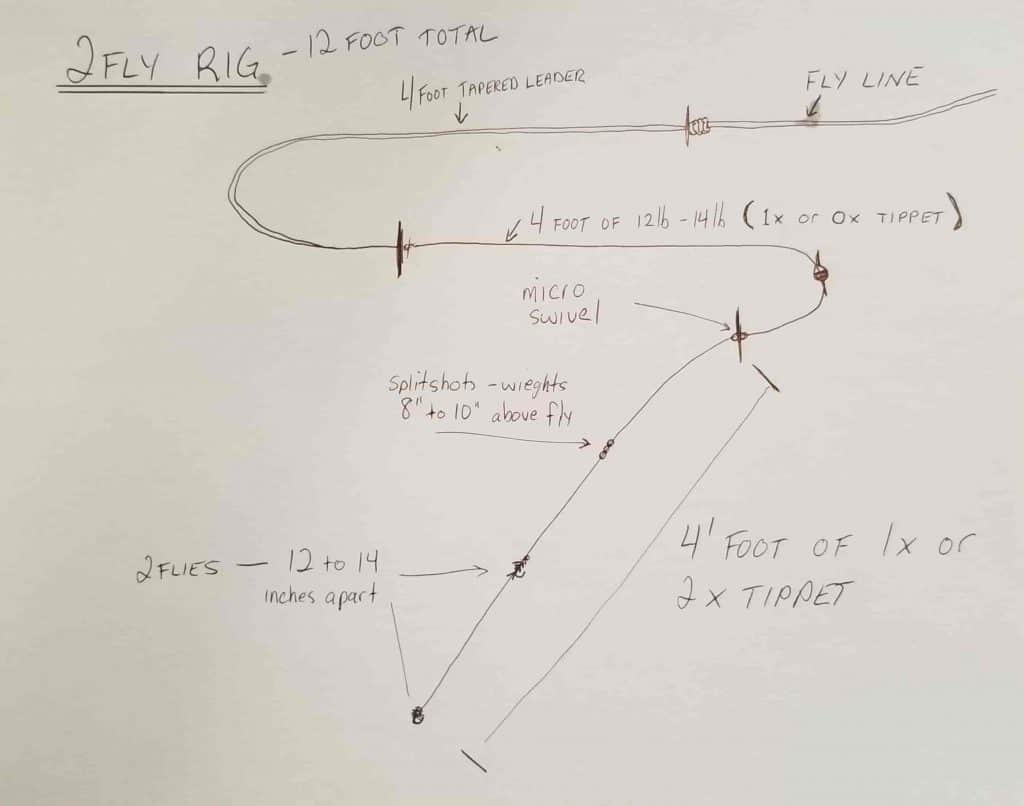

I use this 2-fly leader and indicator rig for fly fishing for salmon and steelhead. When fishing for steelhead I just drop down to 3x tippet or 0.20mm diameter tippet.

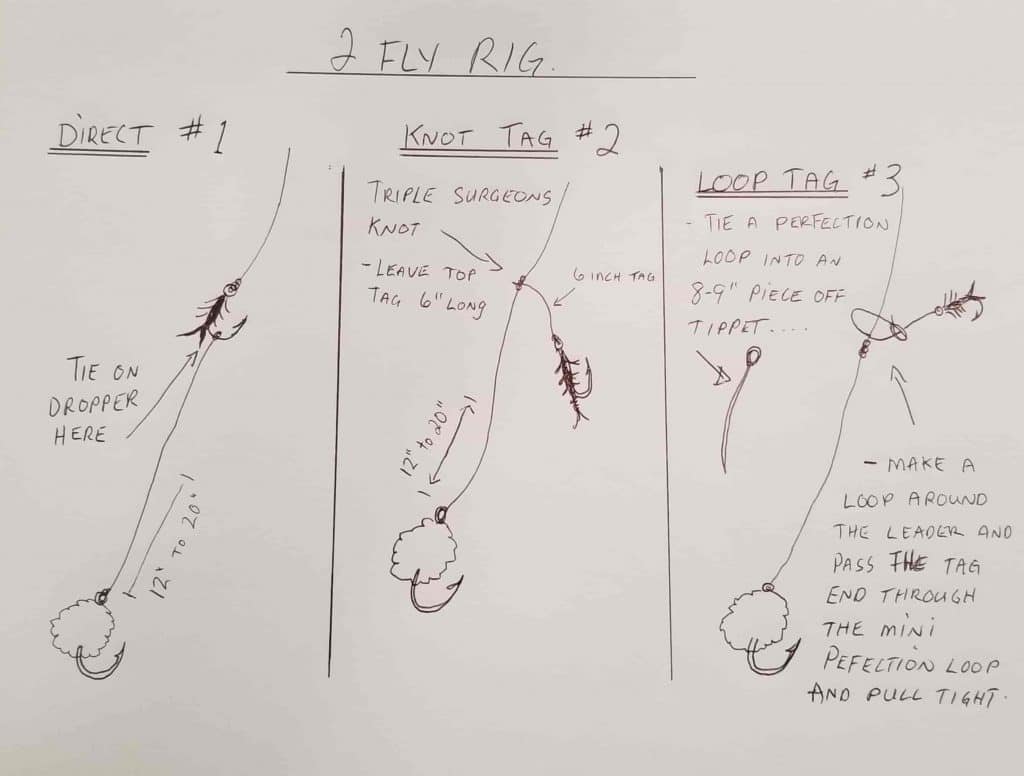

There are 3 ways that I tie on drop fly and all 3 seem to work equally well.

Example #1 to the right is super easy, but the drawback is that if you want to change the top fly, you have two knots to retie. Some anglers will also tie the tag off the eye of the fly, which can work too, but I never use that method.

The 2nd example is also very easy and allows your fly to hang off the main leader, and may provide more movement to the fly. This rarely tangles, so don’t worry about that. The disadvantage to this setup is that you can only change the fly on this dropper tag a few times before it gets too short.

The 3rd example that I use is when the dropper in the 2nd example gets too short. This 3rd example is a replacement tag if your tag gets too short and can be added without needing to cut your triple surgeon’s knot. Just make sure you attach it above the triple surgeon’s knot. I have never seen this slip or break.

An added advantage is that this tag can rotate around the leader, which may provide better action.

I keep my flies about 12 inches apart when the water is dirtier and up to 24 inches apart when the water is super clear. For most conditions, my flies are about 16 inches apart.

I use this same setup for steelhead and salmon, except for salmon, I upsize the tippet and midsection by 2 to 4 pounds. You can also add a 3rd fly to any of these.

Which Fly To Use

In the diagram above, I have a nymph on the top and an egg pattern on the bottom.

My clients often ask which fly they should put on the top and which one on the bottom. How do I choose which goes where?

Although many guides I know put the nymph on the top and the egg on the bottom, probably because they believe the eggs tend to roll along the bottom and stay deeper. This could be true, but . . . .

My simple answer is to put your confidence fly on the bottom, or once you have determined they want more eggs, or more nymphs, or a worm, you put that fly, the one they want, on the bottom.

FYI, there is no rule saying you can’t run 2 or even 3 of the exact same fly, I do sometimes, especially if they all seem to want I specific pattern.

After all, they are not all tight to the bottom in some cases, so putting an egg up high might just work.

As I write this, I’m now in the middle of my busy guide season. It’s hectic, but we are catching a lot of fish, so that is good.

I’m going to need to continue this article at a later date, but WAIT, if you want more and updated info on salmon, with completed articles, and all my tactics in depth,

Check out my other articles at Salmon Fishing – Trout Steelhead And Salmon Experts

Salmon Fishing Gear

Salmon are big and strong and require certain gear that can handle them.

You won’t believe how many rods I’ve seen snap while guys are fighting salmon, or how many reels and drags I’ve seen bust on fast runs.

Not my rods and reels, becuase I use the right gear, but the gear some guys hit the river with is really not suitable for salmon.

To make sure you have all the right gear, from rods and reels, down to line and hooks, be sure you check out my article THE BEST GEAR FOR SALMON FISHING.

MORE ON SALMON FISHING

I’m not sure if you are aware, but I have a new website and it has a lot more UP-TO-DATE and more detailed information. You gotta check it out. at Salmon Fishing – Trout Steelhead And Salmon Experts

Tight Lines,

Graham